Leonard Woolley’s excavations at the ancient Sumerian city of Ur in southern Iraq – or Mesopotomia, ‘the land between the two rivers’, as it was then known – lasted from 1922 to 1934. At the end of the 1926 season, working on a cemetery site containing some 2,500 burials, the excavators uncovered a deep shaft, at the foot of which lay a gold dagger with a hilt of lapis lazuli, and a gold sheath, along with a hoard of copper weapons and a set of little toilet instruments. Nothing of this quality and date had ever been found before in Mesopotamian archaeology.

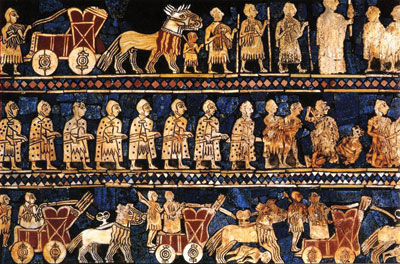

Work in subsequent seasons revealed 16 burials of exceptional wealth. These ‘Royal Tombs’ comprised sunken stone chambers with vaulted roofs, approached down steep ramps cut into the earth. Most had been robbed, but even these often still contained extraordinary treasures, like the ‘Standard of Ur’; made up of mosaic panels of lapis lazuli and mother-of-pearl, it had once formed the sides of the sound- box of a lyre. One rich tomb, that of Queen Puabi (known from a seal buried with her), was found intact. The evidence of this and some of the other tombs revealed an elaborate funerary ritual involving human sacrifice on a mass scale. Woolley talked of ‘the death-pits of Ur’.

The Royal Tombs of Ur described

The grave-goods of the Early Dynastic rulers of Ur were of two kinds. An abundance of rich artefacts signalled their status and equipped them for the afterlife: as well as the golden dagger and the sound-box mosaics, there were two statuettes of a male goat with its forelegs resting on a tree, executed in gold and lapis lazuli; a lyre adorned with a golden bull’s head; gold and silver vessels; jewellery of precious metals and semi-precious stones; a diadem of golden leaves and rosettes; and such lesser items as helmets, weapons, and other war-gear.

More shocking, however, was the presence of attendants. ‘The burial of the kings,’ explained Woolley, ‘was accompanied by human sacrifice on a lavish scale, the bottom of the grave-pit being crowded with the bodies of men and women who seemed to have been brought down here and butchered where they stood. In one grave, the soldiers of the guard, wearing copper helmets and carrying spears, lie at the foot of the steep ramp that led down into the grave; against the end of the tomb chamber are nine ladies of the court with elaborate golden head-dresses; in front of the entrance are drawn up two heavy four-wheeled carts with three bullocks harnessed to each other, and the driver’s bones lie in the carts, and grooms are by the heads of the animals.’

The Royal Tombs of Ur assessed

The richness of the tombs and the grotesque funerary ritual represented by them shed a sharp new light on the origins of civilisation in Ancient Mesopotamia. The implication was of a complex and highly stratified society in which an exceptionally wealthy and powerful elite had been elevated above society to almost god-like status. The range of materials used in the fashioning of artefacts implied wide trade contacts, and the craftsmanship embodied in the objects bore testimony to a hitherto unsuspected level of skill and artistry. This was also, however, a brutal and militaristic society. War-gear featured prominently among the grave-goods, but most striking in this respect were the images depicted on the Standard of Ur, which shows Sumerian charioteers riding down fleeing enemies, Sumerian spearmen leading naked captives before them, and the Sumerian king receiving these unfortunate victims of his army’s prowess. From the underground chambers of the Royal Tombs emerged a picture of a civilisation that was at once dazzling and sinister.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 49. Click here to subscribe

Leonard Woolley’s excavations at the ancient Sumerian city of Ur in southern Iraq – or Mesopotomia, ‘the land between the two rivers’, as it was then known – lasted from 1922 to 1934. At the end of the 1926 season, working on a cemetery site containing some 2,500 burials, the excavators uncovered a deep shaft, at the foot of which lay a gold dagger with a hilt of lapis lazuli, and a gold sheath, along with a hoard of copper weapons and a set of little toilet instruments. Nothing of this quality and date had ever been found before in Mesopotamian archaeology.

Leonard Woolley’s excavations at the ancient Sumerian city of Ur in southern Iraq – or Mesopotomia, ‘the land between the two rivers’, as it was then known – lasted from 1922 to 1934. At the end of the 1926 season, working on a cemetery site containing some 2,500 burials, the excavators uncovered a deep shaft, at the foot of which lay a gold dagger with a hilt of lapis lazuli, and a gold sheath, along with a hoard of copper weapons and a set of little toilet instruments. Nothing of this quality and date had ever been found before in Mesopotamian archaeology.

[…] The Royal Cemetery of Ur, located in modern-day southern Iraq and which came about 500 years after the Başur Höyük cemetery, shows examples of mass adult retainer sacrifices. […]

[…] The Royal Cemetery of Ur, located in modern-day southern Iraq and which came about 500 years after the Başur Höyük cemetery, shows examples of mass adult retainer sacrifices. […]