Alexandra has suffered badly. The once magnificent city has been a quarry for builders throughout the ages. In AD 836 it was robbed to build the city of Samarra in Iraq; in 1167 the magnificent Serapeum – converted by the ruffianly Theophilus into the church of St John the Baptist – was in its turn demolished to form the sea defences. The Crusaders ransacked it in 1365, and ten years later an earthquake wrecked what the Crusaders had left, destroying the Pharos (lighthouse). However, the Ottoman city was built in the harbour area to the north-east, so by 1800 much still survived to be fought over by Napoleon and the British. The real destruction came in the 19th century, when the ruler Muhammad Ali built a new Alexandria over the remains of the old, destroying most of the latter in the process. In 1863-1866 the Arab astronomer Mahmoud Bey was still able to compile a fine plan showing the ancient street grid, but in 1882 the destruction of the Rosetta Gate, to build a new hospital, marked the end of ancient Alexandria.

Alexandra has suffered badly. The once magnificent city has been a quarry for builders throughout the ages. In AD 836 it was robbed to build the city of Samarra in Iraq; in 1167 the magnificent Serapeum – converted by the ruffianly Theophilus into the church of St John the Baptist – was in its turn demolished to form the sea defences. The Crusaders ransacked it in 1365, and ten years later an earthquake wrecked what the Crusaders had left, destroying the Pharos (lighthouse). However, the Ottoman city was built in the harbour area to the north-east, so by 1800 much still survived to be fought over by Napoleon and the British. The real destruction came in the 19th century, when the ruler Muhammad Ali built a new Alexandria over the remains of the old, destroying most of the latter in the process. In 1863-1866 the Arab astronomer Mahmoud Bey was still able to compile a fine plan showing the ancient street grid, but in 1882 the destruction of the Rosetta Gate, to build a new hospital, marked the end of ancient Alexandria.

As a result, the architecture of Alexandria is virtually unknown. Yet Alexandria must have been one of the major influences on the art and architecture of the eastern Roman Empire, and in her new book Judith McKenzie seeks to repair the omission.

McKenzie is an Australian scholar long ensconced at Oxford, who began her studies at Petra, on which she wrote a fine book, The Architecture of Petra, now happily reprinted by Oxbow, price £45. Here, she argued that the architecture of Petra is to a considerable extent based on the architecture of Alexandria, and if we want to see Alexandrine architecture at its best, we should go to Petra. Indeed, she even pointed out the remarkable resemblances between the architecture of Petra and the architecture displayed on the wall paintings of Pompeii: when the Egyptian cults of Isis and Serapis arrived in Italy, they brought with them the accompanying art and architecture. However, since her work at Petra, she has spent 15 years studying Alexandria itself, and this magnificent book is the result.

There are two particular periods when Alexandra was of major importance. The first was in the first centuries BC and AD, when what McKenzie calls ‘the baroque style’ spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean. It is characterised by the broken pediments seen in so many Pompeian wall-paintings, and also by Corinthian capitals, which showed influence from ancient Egyptian volutes. Egypt saw some major changes at this time: Roman styles began to creep in, and there is an interesting chapter in the book on architecture in Roman Egypt, with a reconstruction of the Temple of Amun at Thebes (Luxor) showing its conversion into a Roman legionary fortress, which, for me, makes sense for the first time of this very confusing temple.

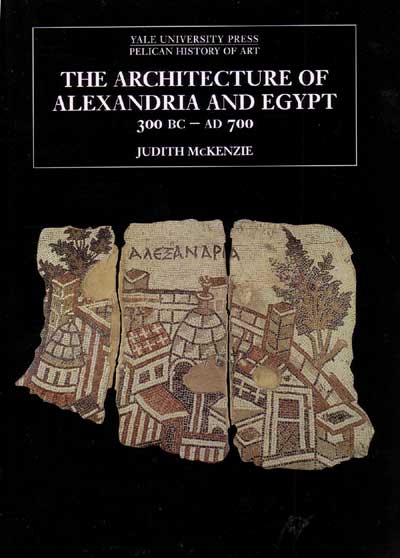

McKenzie’s most subversive chapter comes at the end, when she suggests that Alexandria had a hitherto wholly unrecognised influence on Early Byzantine art. There is a standing problem in Constantinople: what were the sources of the design of the Hagia Sophia with its huge dome, built by Justinian in the 530s? The answer, she implies, is Alexandria, and in an interesting (though at first apparently irrelevant) chapter on Architectural Scholarship and Education in Alexandria, she argues that it was the mechanikoi (architects, engineers, master-builders) and mathematicians working and teaching in Alexandria who worked out the theoretical basis for the great dome. Look closely at the dust-jacket of the book, which shows an architectural mosaic from Jerash, helpfully labelled Alexandria, which features the domes of otherwise unknown churches in Alexandria: are these the forerunners of the Hagia Sophia?

This is an outstanding book, and beautifully written in a Mandarin style; a little old-fashioned, perhaps, but helpfully explaining all the background, and mercifully free from all the jargon and theoretical grandstanding that appears in so much academic writing nowadays. It is very well illustrated not only with her own images, but also with reconstruction drawings by the much-missed Sheila Gibson. This is a book that all those interested in the art and architecture of the eastern Mediterranean, Pompeian wall-paintings, Ancient Egypt, and indeed Islamic architecture should study and learn from. And I must clearly order the reprint of her book on Petra.

Review by Andrew Selkirk, Editor-in-chief

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 34. Click here to subscribe