In Brian Fagan’s latest instalment of all things archaeological that are both exotic and entertaining he looks to the Americas, where he considers irrigation, climate change, and venerable beads.

In Brian Fagan’s latest instalment of all things archaeological that are both exotic and entertaining he looks to the Americas, where he considers irrigation, climate change, and venerable beads.

The last couple of months have been a potpourri of different experiences—lecturing in various places, best of all to the wonderfully enthusiastic chapter of the Arizona Archaeological Society at Sedona; towing a dinghy 1,100 miles from Tacoma, Washington, to home; and delving into the esoterica of rendering grease from reindeer carcasses. (I’m sure the Editor has never had to deal with grease rendering.) So it’s good to get back to my desk to write…

The master irrigators

One of the advantages of advancing years is that you sometimes meet the legendary archaeologists of half a century ago. I was lucky enough to be shown around Snaketown in Arizona by Emil Haury, a Southwestern archaeologist of renowned reputation. He was an expert on the Hohokam of the Arizona Desert, until recently the least known of the ancestors of the current Native American peoples of the Southwest. Haury was, in the final analysis, an excavator who investigated sites such as Snaketown, with its spectacular ball court.

But there is a famous picture of him posing in an excavated Hohokam irrigation canal, which acknowledges the critical importance of irrigation agriculture to people living in such an arid environment. Since Haury’s day, dozens of excavations and surveys in both Tucson’s Santa Cruz Valley and under the sprawling Phoenix metropolitan area have revealed the true genius of Hohokam farmers, who cultivated the fertile spoils of the Gila and Salt River Valleys with elaborate irrigation systems based on gravity.

Irrigation has a long history in the Southwest. Farmers around Tucson to the south diverted water from the Santa Cruz River by at least 1500 BC and probably earlier. After about AD 450, major irrigation systems developed on the Salt and Gila River Valley, today under and around Phoenix. At first, village communities maintained the canals and allocated water to individual fields.

In time, however, the founding families, who had first acquired land near the major canals, eventually controlled water allocation, which they surrounded with complex ritual. The elaboration of Hohokam irrigation is one of the great, if unspectacular, discoveries of North American archaeology in recent years. We have so much more to learn about one of the Southwest’s lesser-known agricultural societies of a thousand years ago.

Maya drought from a different angle

The Cariaco deep-sea core off Venezuela in the Caribbean is becoming a major climatological yardstick by any standards. Its fine laminations also record major drought cycles during and after the 8th century AD that apparently had serious consequences for the ancient Maya.

The Maya reaction to such droughts involved not only major changes in settlement patterns, but also numerous, still little known, water rituals. We know of one of these cults from remarkable discoveries in caves in Belize. The Maya rain god was Chac, often shown on bark codices residing in a cave and creating rainfall by pouring water from an upturned jar. Between AD 680 and 960, the Maya of western Belize created a drought cult centered on this powerful deity.

At Chechem Ha Cave, Holly Moyes, Jaime Awe, and other colleagues have mapped 300m (984 feet) of tunnels and the central chamber. By plotting the distribution of charcoal specks from the Maya visitors’ flaming torches in their excavations and radiocarbon dating them, the team showed that the local people visited the central chamber to perform rituals around a central stalagmite and pool. They occasionally left broken potsherds behind them. After AD 680, the visitors deposited more clay vessels in the cave, 51 of them complete pots, sometimes inverted, lying throughout the cave, some in parts of the cavern never visited before. The Maya left more clay vessels behind them between AD 680 and 960 than at any other time. Many of the pots have wide mouths of a type employed for collecting water, just like those used by Chac.

The excavators believe that the vessels were gifts to the rain god. The higher density of pots coincides with a lengthy dry period in the region, known from a stalagmite record in a cave only 15km away. When Moyes and Awe surveyed 53 other caves in central and southern Belize, they found large, intact jars lying on ledges and floors in many of them. They believe that they have recovered evidence of a widespread and hitherto unknown drought cult, which coincides with the climatic data for arid conditions from several climatic sources. So much for the old saw that ritual is the final resort of troubled excavators!

Bead upon bead

Glass beads were once the bane of my existence. The formidable Gertrude Caton-Thompson, who proved that Great Zimbabwe in southern Africa was of African origin in 1929 (see CWA 35), was one of the great proponents of glass beads as a way of dating ancient archaeological sites in the days before radiocarbon dating. I met her once when she was in her 80s and suffered through a prolonged lecture on Indian Ocean glass beads, carried in their thousands far inland from the East African coast. They are far from precise chronological markers, but I counted thousands of them in my day—a mind-deadening activity at best. But my hours of bead sorting piqued my interest in a recent discovery in Georgia. A cache of more than 70,000 trade beads has come from St Catherine’s Island off Georgia, the largest repository of Spanish trade beads ever recovered in the Americas.

The beads come from the 18th century Mission Santa Catalina de Guale, a major source of grain and the capital and administrative center of the province of Guale in Spanish Florida for more than a century. More than 130 bead forms come from the mission cemetery, many of them of Chinese, Dutch, French, and Venetian origin. The excavators believe that the beads were traded from St Augustine, where the missionaries and colonists were perennially short of grain. Many of the beads come from areas around the altar. Numerous specimens lay with the bodies of high status children, which suggests that privilege had a significant role on Guale society during the early 18th century.

The specialists who counted and classified the Guale beads may have been as bored as I was, but they had the consolation that they throw important light on life on the Spanish frontier over 300 years ago.

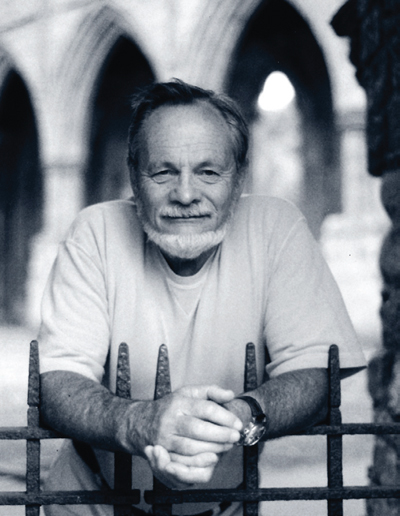

Brian Fagan is the author of numerous popular books on archaeology and Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He hopes he never has to classify glass beads again.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 36. Click here to subscribe