Khentkawes is hardly a household name. The historical record passes over this elusive figure without comment, while the scraps that testify to her existence could seem worthy of no more than a stale footnote in the annals of Ancient Egypt. Yet archaeology shows otherwise. It is revealing an exceptional and powerful lady who lived during the mid 3rd millennium BC.

Khentkawes is hardly a household name. The historical record passes over this elusive figure without comment, while the scraps that testify to her existence could seem worthy of no more than a stale footnote in the annals of Ancient Egypt. Yet archaeology shows otherwise. It is revealing an exceptional and powerful lady who lived during the mid 3rd millennium BC.

This was the time of the fourth dynasty, a golden age that bequeathed the magnificent royal pyramids at Giza. But while Pharaoh Khufu could found a great pyramid that was, for nearly 4,000 years, the tallest man-made structure on Earth, just half a century later his royal line was waning, and the scale of its pyramids rapidly diminishing. Khentkawes’ fate was bound to the shadowy events that brought down the fourth dynasty and gave rise to the fifth; events with which she may well have been intimately involved.

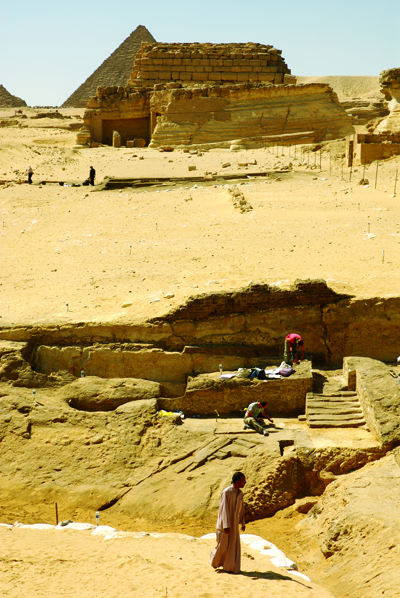

When Khentkawes died, she, too, was interred on the Giza plateau, in one of the most fascinating tombs in the ancient necropolis. Her unique resting place was fashioned from a 10m-high bedrock pedestal crowned by a stack of carefully laid blocks. This distinctive monument is a cross between a pyramid and a flat-roofed rectangular tomb known in Arabic as a mastaba, because of its resemblance to a bench. The large, rectangular entrance to Khentkawes’ ground-floor mortuary chapel is equally reminiscent of a garage. The tomb is only part of a wider cult complex, and its curious design hints at Khentkawes’ exceptional status. That is why her monument has been a key feature of Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA) Giza research with the Supreme Council of Antiqities and Vice Minister for Culture, Dr Zahi Hawass, since 2005. A combination of excavation and laser survey has revealed her tomb and its environs in unprecedented detail, casting new light on the end of the fourth dynasty.

A life less ordinary

Everything that is known for certain about Khentkawes was carved into her extravagant, red-granite chapel gateway. Although heavily weathered, a faint hieroglyph inscription and a relief image of a seated figure have survived the shifting desert sands. But these tantalising snippets of information are frustratingly ambiguous. The inscription can be translated in one of two ways, revealing that the deceased was either ‘Mother of the Two Kings of Upper and Lower Egypt’, or, ‘Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, and King of Upper and Lower Egypt’. Either way we are dealing with a queen, but if the second reading is accurate then this is a queen who went on to assume the mantle of pharaoh and rule in her own right. This would make her one of a select group of women who adopted a supposedly male title and role, when either the heir was too young to rule, or the royal bloodline was exhausted.

The seated image of Khentkawes probably holds the answer. The telltale traces of a uraeus, the deadly spitting cobra on a pharaoh’s crown, and a ceremonial strap-on beard can arguably be faintly discerned on the weather-worn stone. Yet a contrary interpretation casts the crown as an Egyptian queen’s trademark vulture cap, and the beard no more than a trick of the centuries’ scouring. It is certainly true Khentkawes’ name is not rendered in a cartouche, the oblong seal that often denotes a pharaoh. But none of this is conclusive, and when considered alongside her exceptional mortuary complex the possibility we are dealing with a queen who became king is compelling.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 44. Click here to subscribe