What was life like for the first farmers in Europe? Cutting-edge bioarchaeological research on skeletons from the Vedrovice cemetery in the Czech Republic is providing illuminating answers. Paul Pettitt and Marek Zvelebil report.

What was life like for the first farmers in Europe? Cutting-edge bioarchaeological research on skeletons from the Vedrovice cemetery in the Czech Republic is providing illuminating answers. Paul Pettitt and Marek Zvelebil report.

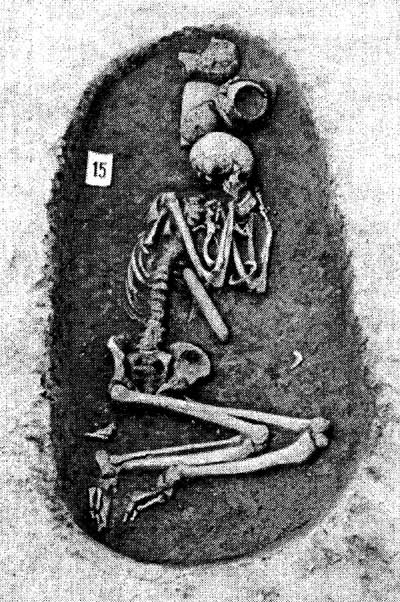

The man oozed status. He died in the 53rd century BC, in his early 30s. Although his age at death was fairly typical for his people, he died violently. Someone had delivered a crushing blow to his skull. Perhaps he had suffered pains ever since the wound was received, as an attempt had been made to trepan his skull at the point of the wound – a remarkably rare example of early surgery. But it seems that his injuries troubled him until the day he died, as he was buried on his left side, his hands placed close to his temples as if to relieve the pain.

As an experienced elder of the community he had achieved a high status. His grave, in the so-called Vedrovice cemetery in Central Europe, contained a jug and a bowl that were probably his eating and drinking vessels in life, an adze made of a stone imported from a source as distant as the Bohemian Massif or Western Carpathians or the Balkans, a flint blade from the Krakow Jura, a spondylus shell necklace, marble beads, four perforated deer teeth, and two grinding stones.

A large amount of red ochre was found around his upper body and under his skull, red being, perhaps, the colour of transformation and passage from one life to another. He wore pendants and a bracelet made from spondylus shells that originated in the Mediterranean. Born at or near Vedrovice, he was a local man and remained in the area until his death. Throughout his life he had a varied diet of wild and domestic plants and animals, but, more than his fellow villagers, he had enjoyed regular access to meat.

Vedrovice and the spread of LBK

The man, known as ‘Burial 15/75’, belonged to the Early Neolithic, the period in which agriculture – with its origins in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East – was replacing the old traditions of hunting and gathering across Europe. Specifically, he belonged to the Linear Pottery Culture or LBK, a loose agglomeration of agricultural hamlets focussed on longhouses and bound by a common world view and cultural tradition. His grave at Vedrovice lies within the earliest-known LBK cemetery in the Czech Republic.

The LBK tradition, characterised by pottery decorated with linear bands, originated out of the Balkan Neolithic. How domesticated life spread to Vedrovice is one of the major questions of our research and that of fellow prehistorians. Certainly, within a few centuries of its appearance at Vedrovice, the LBK culture and traditions would spread right across Central Europe and as far west as the Paris Basin and The Netherlands.

This spread of agriculture in Europe – literally a domestication of the continent – was a revolutionary development in human history. It opened up a whole range of new possibilities for people who were otherwise solely reliant upon gathering and hunting of wild resources. Now, plants and animals could be brought under clear control, and support larger population sizes that could be gathered together in permanent communities. New relationships between people and their resources opened up new areas of the landscape for exploitation. New traditions were introduced, in ceramics, chipped and polished stone tools, but perhaps most impressive was the development of the LBK longhouse – the largest structure Central Europe would see until the Iron Age.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 32. Click here to subscribe