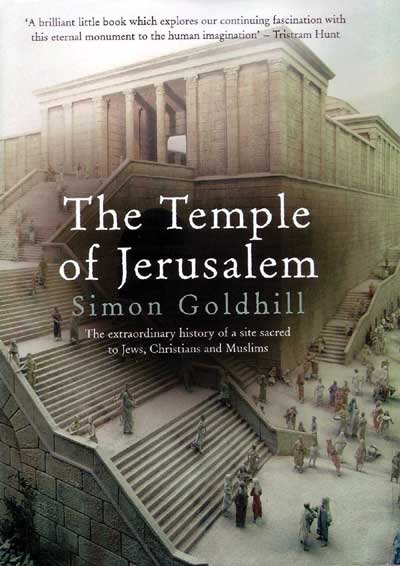

The Temple of Jerusalem is one of the most important non-existing buildings in the world. Just what was it and why was it important? In a slim volume, The Temple of Jerusalem (Profile books, £15.99), Simon Goldhill, Professor of Greek Literature and Culture at Cambridge, looks at the temple in three different stages.

The Temple of Jerusalem is one of the most important non-existing buildings in the world. Just what was it and why was it important? In a slim volume, The Temple of Jerusalem (Profile books, £15.99), Simon Goldhill, Professor of Greek Literature and Culture at Cambridge, looks at the temple in three different stages.

The first temple was that built by Solomon, to whom Professor Goldhill neatly avoids giving a date. But judging by the measurements given in the Bible, it would have been about two thirds the size of the Parthenon and was magnificently decorated. But it was destroyed by the Babylonians in 587 BC, and no sign of it has ever been discovered. Nevertheless, it established the two unique characteristics of the temple: firstly, it was a temple to the name of God – there was no statue of the god due to the Commandments. And secondly, it was the only temple of the Jews, it had a monopoly on sacrifices, and was the only place where sacrifice could be made (much of the Old Testament is devoted to those backsliders who made sacrifices on false altars).

Following its destruction, the second Temple was built by Zerubbabel in 515 BC and re-dedicated by the Maccabees, following their revolt in 161 BC; it was nowhere near as grand as the first.

The third Temple – and we have to be careful of our numbering here – for the third Temple is meant to be a temple of the future, and it is only pesky archaeologists who divide up Temples 1, 2 and 3; but the third Temple was that built by Herod the Great (37-4 BC), on the huge and lavish scale that only dictators can achieve. Perhaps the greatest – and certainly the most long-lasting construction was the huge platform on which it was to stand. On the platform was a series of courtyards, getting progressively holier, until at the centre, was the temple itself. The Temple did not last long; it was destroyed by Titus in AD 70.

The destruction of the Temple affected Jews and Christians differently. For the Jews, it was catastrophic. The Temple had a monopoly on sacrifice, which in the ancient world, was the major means of communication between man and God. As the author points out, the Temple of Herod the Great must have been an incredibly smelly place, with the smell of the incense combining with the smell of roasting meat – every family had to bring a lamb to be sacrificed at the Passover. But no temple meant no sacrifices, and instead a new form of religion grew up, based on prayer and scholarly discussion. The Temple was replaced by the synagogue, the priests by the rabbis (who are not priests), and thus the study of the Talmud became a way of reconstructing the temple in the mind.

The Christians saw the destruction of the Temple differently. They saw its destruction as a satisfying example of a punishment of the Jews, and when Christianity took over, the Roman Temple on the site was demolished and the site was deliberately turned into a rubbish dump. However, it also meant that they too rejected all animal sacrifice, a rejection which is one of the major characteristics of Christianity: the crucifixion becomes the sole sacrifice. In a further development, the Temple is transformed into each Christian’s body, leading to the Christian obsession with purity; the sexual purity of the body becomes a defining category of holiness. Mind you, the rejection of the physical temple did not last long, and by the time that Byzantium flourished, huge churches were being built, followed by the cathedrals of the Middle Ages. But though they may have been filled by the odour of incense, they were never sullied by the odour of burnt sacrifice.

It was the Muslims who actually did something about the Temple Mount. According to the Koran, Mohammed made a night journey from Mecca to Jerusalem and back, landing on the Temple Mount, thus making it into a very holy site. When the Muslims conquered Jerusalem, they were horrified to find that the Christians were using it as a rubbish dump, and they therefore built over it the Dome of the Rock, which remains to this day one of the most stunningly beautiful buildings in the world. When the Crusaders captured Jerusalem, they turned it into the Temple of Our Lord, but when Saladin conquered it, it became once again a Muslim site. Subsequently it has frequently been taken as being ‘the’ Temple and many artists such as Raphael, in his Marriage of the Virgin, have depicted it as being ‘the’ Temple.

Since then, each generation has reconstructed it in its own image, and frequently, indeed, built models of their beliefs; currently, a Suffolk farmer, Alec Garrard, is building a splendid model of it in his barn. The templars and freemasons have appropriated it, each in their own often alarming ways. Archaeology has played a minimal role – all the religions concerned being terrified of what might be discovered. There have only ever been two excavations, both semi-illicit, but both highly successful. In the 1870s, Capt Warren excavated for the Palestine Exploration Fund and found the network of drainage tunnels which underlie the mound; and in the 1970s Professor Mazar found the steps leading up to the Temple.

I found this an enthralling book with a superb mixture of historical narrative and philosophy. It is illustrated with cheap black and white illustrations but these achieved the almost unheard-of feat of fitting perfectly with the text – everything that needs to be illustrated is illustrated. I think that Jews, Christians and Muslims alike, providing they are prepared to have their beliefs examined and sometimes challenged, will find much to illuminate and inspire them. Even non-believers will find much that is stimulating and enjoyable.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 9. Click here to subscribe