In 1921, the Swedish geologist Gunnar Andersson and his palaeontological assistant Otto Zdansky, an Austrian, discovered some intriguing fossil bones in a complex of Pleistocene-era caves near Peking. Dragon Bone Hill is the English translation of the local Chinese name (Longgushan) of the caves that are internationally known as Zhoukoudian.

In 1921, the Swedish geologist Gunnar Andersson and his palaeontological assistant Otto Zdansky, an Austrian, discovered some intriguing fossil bones in a complex of Pleistocene-era caves near Peking. Dragon Bone Hill is the English translation of the local Chinese name (Longgushan) of the caves that are internationally known as Zhoukoudian.

A galaxy of international scientists of several complementary disciplines soon gathered in China to work on these fossils. Among them was a brilliant young Canadian anatomist, Davidson Black, who, on the basis of rather rudimentary evidence then available, daringly assigned a genus and species to the source of these bones in 1927, namely Sinanthropus pekinensis (popularly known as Peking Man). After Black’s untimely death in 1934, he was succeeded by an eminent former German professor of anatomy, Franz Weidenreich – who was responsible for the wide-ranging reconstruction of Peking Man’s physical and mental attributes. Also among the international team was the French palaeoanthropologist, Father Teilhard de Chardin, who, with remarkable skill, kept the world scientific community informed of the discoveries at Zhoukoudian through incessant letter-writing and globe-trotting. Last, but not least, were the Chinese archaeologists, Pei Wen-zhoug and Jia Lan-po, who made extraordinary discoveries of a number of fossil bones, including nearly complete skulls of Peking Man.

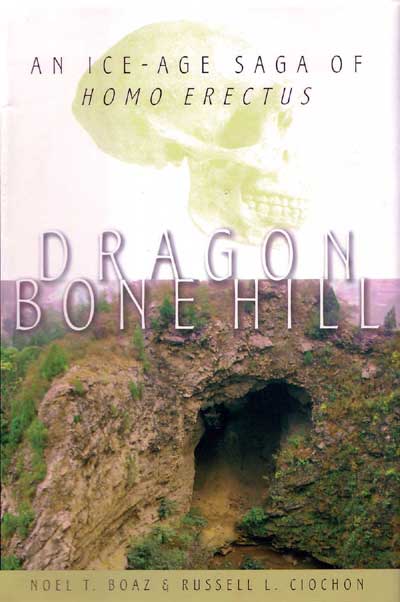

This is now the subject of an exciting new book, Dragon Bone Hill: An Ice Age Saga of Homo erectus, (OUP New York, price US $30: available from Amazon for £15.22) by Noel T Boaz, a Professor of Anatomy, and Russell L Ciochon, the Chairman of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Iowa. The book is written in a very vivid and readable style – full of amusing flourishes – and aims at informing and educating the intelligent layman with a remarkable facility of language: all technical terminology is immediately explained in everyday speech.

The authors’ main scientific conclusions – the result of detailed interdisciplinary analysis of a mass of data – are that: Peking Man originally came from Africa; was a scavenger of the prey of more powerful carnivores (e.g. giant hyenas); had some cannibalistic traits; could fashion primitive stone tools; had a rather small brain but a very thick-boned skull; had a rudimentary hold on the use of fire; and probably did not possess the faculty of speech.

I found the early chapters of the book to be particularly captivating. They describe the discovery of the site and efforts to infer the likely lifestyle of the homo erectus who lived in those caves between some 700,000 and 400,000 years ago. It was with increasing interest and bated breath that I read the authors’ masterly reconstruction of events leading to the most tragic disappearance of all the original fossils excavated from the Dragon Bone Hill throughout the 1920s and 1930s – when they were all ready and wrapped up in two wooden boxes for being shipped out to the USA. But, at the crucial and fateful moment, a force majeure struck in the form of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour on 8 December 1941, and the incarceration of several major players in the drama, as enemy aliens, by the Japanese occupying forces in Peking. The whole account reads like a detective story worthy of a Conan Doyle – but it covers not imaginary events but, as the authors put it, ‘the single greatest loss of original data in the history of palaeoanthropology’.

I thoroughly recommend the book to all those who are even remotely interested in areas connected with anthropology and/or human evolution. Serendipitously, I received the book from CWA just after I had written my postcard on Peking Man’s Cave for this issue of the magazine!

– Saeed Durrani

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 5. Click here to subscribe