All of this issue’s features come from members of the Egypt Exploration Society, Britain’s leading Egyptology Society. Here, Chris Naunton recounts the trailblazing story of the Society.

All of this issue’s features come from members of the Egypt Exploration Society, Britain’s leading Egyptology Society. Here, Chris Naunton recounts the trailblazing story of the Society.

Over the past 125 years of archaeological excavation in Egypt, the Egypt Exploration Society (or EES) has made discoveries that have changed our very understanding of Egyptian history and culture. Our work has ranged from excavation at Egypt’s great sites – such as Saqqara – to endeavours aimed at understanding more about the Ancient Egyptian landscape.

While our expeditions are led by professionals, most of our members are non-professionals and to this day, the Society remains true to its original remit: ‘to advance the education of the public’ and ‘to raise the knowledge, awareness and understanding of all aspects of ancient and Medieval Egypt’.

But to go back to the beginning: the driving force behind the EES was the English traveller and writer Amelia Edwards (1831-1892).

The indefatigable Amelia

Amelia – she is known affectionately to Egyptologists by her first name only – was raised in a comfortable middle-class household and, perhaps like many daughters of comfortable middle-class households, longed for adventure. She travelled widely throughout the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s but it was her travels in Egypt during 1873-1874 that had an especially profound effect on her. By 1880, Amelia was hell-bent on bringing ancient Egypt into the popular consciousness. She was particularly concerned for the welfare of Egypt’s monuments, and over the course of the next two years she began gathering support among the scientific community for the establishment of a fund to support excavations in Egypt.

On 30 March 1882, she and her colleagues in England announced in The Times that ‘A Society has been formed for the purposes of excavating the ancient sites of the Egyptian Delta, and the scheme has a reasonable prospect of success’. The proposal drawn up by Amelia and her colleagues had received the approval from, among others, the Archbishop of Canterbury, several bishops, the chief rabbi, the poet Robert Browning, and Sir Erasmus Wilson, who had paid for the transport of Cleopatra’s Needle from Egypt to London. In the months following the meeting, Wilson pledged £500 to the Egypt Exploration Fund (as the EES was then known). This was enough to set the ball rolling.

The expeditions begin

The Fund’s first excavator was Edouard Naville, the Swiss Egyptologist, and with the blessing of Gaston Maspero, head of the French-run antiquities service in Egypt, Naville set out in January 1883 for Tell el-Maskhuta which, it was hoped, would shed light on the route of the Biblical exodus. In order to broaden the appeal of the Fund’s work, its founders had felt it best that it concentrate ‘on sites of Biblical and classical interest’, and Naville’s work – particularly his identification of Maskhuta with the Biblical city of Pithom (although now discredited) – aroused much public interest.

At the first General Meeting of the Fund on 3 July 1883, the accounts showed a healthy balance, and it was proposed that a copy of Naville’s volume (the first ‘memoir’) should be sent to all subscribers to the Fund, thus establishing the fundamentally important principle – which continues today – that the results of the Fund’s work be published within a year, and disseminated to the membership in partial return for their support. Despite announcing to subscribers that the many objects discovered by the Fund would remain in Egypt as the property of the Boulak Museum (the forerunner to the present Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square, Cairo), the Fund was allowed to remove two objects – a votive statue of a falcon and a naophorous statue of a man named Ankhkherednefer. It was agreed that both should be donated to the British Museum, where they can be seen today on display in the Egyptian sculpture gallery.

For its second season, the Fund engaged the services of another excavator, Flinders Petrie. The so-called ‘Father of Egyptology’, Petrie was a man of unparalleled energy and ingenuity. His first work for the Society was at Tanis, a site which was identified with the Biblical city of Zoan. The site is now best known to visitors for its temple but it was also the location of a substantial settlement, and Petrie’s work in the ordinary dwellings represented a new direction for archaeology. Petrie was among the first to recognise the importance of objects other than those that were aesthetically appealing or bore inscriptions, and this led him to develop techniques for the rigorous, scientific excavation of sites and thorough recording of finds of all types. He was particularly fortunate that many of the houses at Tanis had been burnt, leading to the preservation of numerous objects of the kind that were of little intrinsic value to robbers, or indeed to old-fashioned Egyptologists, but which Petrie recognised would be invaluable in enhancing our understanding of the daily lives of the Egyptian population.

At the end of this season, Petrie was able to bring home a considerably greater number of objects than Naville had been able to export previously, and the Committee agreed, at a meeting in October 1883, that a selection of objects be again donated to the British Museum, but also ‘that the meeting present to the Museum of Boston, United States, a second selection … and other selections to the museums of Bristol, Bolton, York, Liverpool, Sheffield, Edinburgh, and Geneva, to Charterhouse School…’. And so, almost for the first time, scientifically excavated – provenanced – objects were distributed to institutions throughout Britain and overseas. In many cases EES objects would come to form a very substantial part of these collections, but not before they were shown off to the public at special exhibitions organised at the end of each season.

In its third year, the Fund was able to support the efforts of both Naville and Petrie in the field and by this time they were joined by a young Egyptologist, Francis Llewellyn Griffith. As there was no formal tuition in Egyptology available in Britain at this time, Griffith had taught himself Egyptology. He seems rapidly to have mastered the Egyptian language and Egyptological literature and was quickly appointed as official student of the Fund. In the course of the next few seasons he, Petrie and Naville excavated a series of further Delta sites, including the fortified camp at Tell Dafana and the temple of the cat goddess Bastet at Tell Basta. Each season brought significant results both in terms of the advances in knowledge, and in objects brought home for distribution.

Reading Egypt’s riches

Alongside their excavation work, Petrie and Griffith spent much of their time in Egypt field-walking sites and conducting large-scale surveys of vast areas looking for potential sites for thorough investigation.

One such excursion, in 1886-1887, provided Griffith with his first experience of Upper Egypt (Southern Egypt) where standing-monuments survive in better condition and in greater numbers than in the Delta (Northern Egypt), to which he had become accustomed.

To this young Egyptologist it must have been clear how much could be learnt from these monuments without any need for the expensive and time-consuming business of excavation, but also that if the greatest gains were to be made from them, then urgent action was required, since so many sites were threatened with destruction. By 1889, Griffith proposed the establishment of an epigraphic branch of the Fund, which he hoped would record Egypt’s standing monuments within a year or two. Though his proposal was hopelessly optimistic in scope, the principle was nonetheless enthusiastically received, and by the winter of 1890 the first mission of the Archaeological Survey of Egypt was led into the field under the direction of Percy Newberry.

The first mission’s brief was to concentrate on recording the decoration and architecture of a series of tombs in Middle Egypt, including those at Beni Hasan (such as at the glorious depictions of birds from the tomb of Khumhotep II, c.1900 BC, shown above).

In 1895, a third branch of the Fund’s activities was established. Bernard Grenfell, a young Oxford classicist who had worked for Petrie at Coptos, had purchased over 200 papyri in 1893-1895, and now persuaded the Committee of the EEF to expend some of its funds on this aspect of ancient Egyptian civilization.

In 1895, he and archaeologist D G Hogarth, undertook exploratory excavations at Bacchias and Karanis in the Faiyum. The early results were promising enough for Grenfell to telegraph his Oxford colleague, Arthur Hunt, to join him, and the Fund was persuaded to support a second season of excavations, at Bahnasa, ancient Oxyrhynchus.

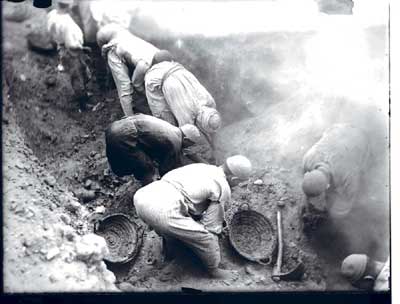

Here, the team began uncovering papyri by the basket-load, and by the end of the season they had found enough papyri to keep scholars occupied for generations: 150 of the most complete papyrus rolls were handed over to the Egyptian authorities in Cairo but the remainder – 280 boxes of papyri – were brought back to England. Among these early finds was a fragment preserving a previously unknown Logia Iesu – ‘the sayings of our Lord’- which, it was subsequently realised, formed part of the gospel of St Thomas. The Logia were published within six weeks of the arrival of the papyri in England in the form of a pamphlet which sold 30,000 copies.

Onwards and Upwards

By the end of the 19th century, the Society was sending several teams into Egypt each year, and had established itself as one the foremost archaeological institutions working anywhere in the world. The distribution of objects and publications had brought it to the attention of scholars and enthusiasts around the world, and its discoveries were widely publicised in the international press, notably in National Geographic in the States and The Illustrated London News in Britain.

In subsequent years, the Society rose yet further, and undertook major projects at Abydos (see this issue’s Books), Saqqara, the royal city of el-Amarna, and at the New Kingdom temple-town sites at Sesebi and Amara West in Sudan, in addition to numerous smaller projects elsewhere. In the 1950s and 1960s, the EES was the British government’s representative in the campaign to rescue the monuments of Lower Nubia from the waters of Lake Nasser. Teams led by Walter Emery and others worked at the vast fortress site of Buhen and at the hilltop site of Qasr Ibrim, which featured evidence of activity from the New Kingdom until well into the Medieval Period.

From its beginnings the Society has worked at some of the richest archaeological sites in Egypt but without ever losing sight of the fact that what was important was knowledge, and that if sites and monuments were to be looted or destroyed, the greatest loss would to be our understanding of ancient Egyptian culture. The Society has never been into treasure hunting (it is interesting to note that the EES had already celebrated its 40th birthday when Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun after years of excavation in the Valley of the Kings).

Nonetheless, the results of the Society’s work have often been spectacular. These include the discovery of a shrine dedicated to the god Hathor, replete with cow statue from Deir el-Bahri, and the dramatic mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut, excavated by the Society in the 1890s. Also of note is the sculptor’s model of Nefertiti from Amarna, a stunning piece discovered by the EES, and now on display in the Cairo Museum. In addition, several EES-excavated objects, such as the statue of the steward of Memphis, Amenhotep from Abydos, are featured prominently in the Egyptian sculpture gallery and elsewhere in the British Museum. Indeed, EES objects appear in collections across the world, where they are seen by millions of visitors every year and remain the focus of researchers’ attentions.

The Society’s publications, the record of 127 years of survey, excavation and epigraphic recording, remain, in most cases, indispensable sources for the study of the monuments concerned. No research into important Egyptian sites, such as the cities of el-Amarna or Memphis, can be undertaken without reference to the relevant EES memoirs. No study of Predynastic burial customs can be contemplated without recourse to EEF volumes on the cemeteries at Abydos, El-Amrah and Mahasna. Likewise, our understanding of the Egyptian practice of burying animals would be immeasurably poorer were it not for the Society’s work at the Bucheum at Armant, a cemetery of sacred bulls, or the discovery the Sacred animal necropolis at Saqqara, to name but a few of our projects. Yet none of this work would have been possible without the support of our members, whose donations and subscriptions to the Society make these discoveries happen.

Amelia Edwards would have been proud that the Society she founded 127 years ago has achieved so much since then. She may even have smiled wryly at the knowledge that many of the things that preoccupied her in the early days – fundraising, the importance of the subscribers, the need to let the world know the results of the Society’s efforts in Egypt- remain just as relevant today.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 36. Click here to subscribe