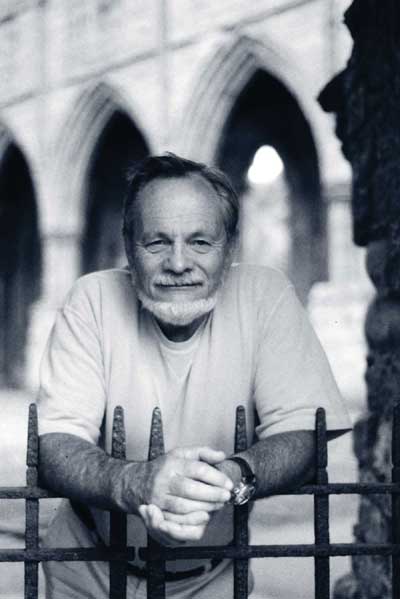

Brian Fagan is one of America’s best-known archaeologists. British by birth he is the Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of many books on archaeology. We recently had the pleasure of meeting up with Brian who was visiting the UK working on a story about the future of Stonehenge for the World Monuments Fund. As a man with his ear to the ground, we asked him to write us a column about things archaeological that are both entertaining and exotic.

Brian Fagan is one of America’s best-known archaeologists. British by birth he is the Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of many books on archaeology. We recently had the pleasure of meeting up with Brian who was visiting the UK working on a story about the future of Stonehenge for the World Monuments Fund. As a man with his ear to the ground, we asked him to write us a column about things archaeological that are both entertaining and exotic.

Stories to dine out on

Having just been to Stonehenge, I was reminded of the entrancing image of the antiquarian William Stukeley dining atop one of the trilithons on summer’s day over two centuries ago, where, he said, there was space enough for ‘a steady head and nimble heels to dance a minuet.’ He may never have done so, and cannot have had many dinner guests, but it’s a lovely story.

Archaeology thrives on apocryphal tales like this. Henry Rawlinson’s ‘wild Kurdish boy’ clambered over the sheer rock face at Behistun in Iran in the 1830s. Maria, the 9 year old daughter of the Marquis de Sautola was bored with his muddy excavations, so she wandered off with a lantern to explore Altamira Cave. ‘Toros! Toros!’ she cried, and the rest is archaeological history.

Or is it? The debunkers are hard at work in the byways of the early days. Writing in a recent issue of History Today magazine, Desmond Zwar effectively overturns one of the legends surrounding the discovery of Tutankhamun. Richard Adamson, a former soldier, claimed that he spent seven years sleeping in the royal tomb at night as Howard Carter slowly cleared it. He was feted as the last survivor of the opening at the British Museum Tutankhamun exhibition in 1972.

Zwar used the research of another journalist, Chris Ogilvie-Herald, who ferreted out Adamson’s marriage certificate and the birth records of his sons, three of whom were born in England while he was allegedly in the Valley of the Kings. These documents listed Adamson as a motor mechanic and bus conductor in Portsmouth during the years of the tomb clearance. So much for firsthand accounts! Is nothing sacred? Perhaps other historical spoilsports will tell us that Maria de Sautola never stumbled on the Altamira bison paintings? If they do, so be it, but I can’t help feeling that archaeology will be a little duller as a result.

Why practice is better than theory

Sailing on a windy day in an open boat certainly focuses the mind, especially if you are just back from a dunking up to the waist in the chilly 8-degree waters of Alaska’s Cook Inlet. I own a modern version of an old fashioned Scandinavian yawl, whose ancestry goes back to Norse fishing boats. As we punched our way to windward with a deep reef in the sails, I pondered the sometimes-extravagant voyages proposed by some archaeologists to people the Americas and Australia. I’m sorry, but you cannot safely paddle a dugout canoe, however large, in moderate Pacific ground swells.

Not enough archaeologists are small boat sailors, and if they were they would not claim, as some do, that bold Indian mariners paddled down the exposed Pacific coasts of Washington, Oregon, and northern California. Even modern-day yachts equipped with all the electronic razzledazzle of the 21st century tread carefully in these waters. Some of those who research and write about ancient voyaging and watercraft would do well to get seasick occasionally. If there is one characteristic of sailors without diesel engines, it is their inherent conservatism. The 19th century British fisherfolk, who plied their craft under oar and sail, rarely went out when the wind blew at over 25 knots, or, if you are a nautical purist, Force 6 on the Beaufort scale.

Climate change is nothing new

Dugout canoes are a far cry from the sophisticated doublehull sailing canoes of the ancient Polynesians. They used such craft to sail from west to east across the Pacific against the prevailing trade winds. Inspired experiments by the small boat sailor David Lewis in the 1960s showed that traditional Polynesian navigation was alive and well. Lewis apprenticed himself to a master pilot and learned how to cross hundreds of kilometres of open ocean out of sight of land with the aid of the sun, stars, and swell patterns – to mention only a few phenomena. His mentor even used his swinging testicles to determine the direction of intersecting swells. The lengthy voyages of the Hawaiian canoe Hokule’a are eloquent testimony to the efficiency of ancient Polynesian navigators. She sailed from Mangareva Island to remote Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in 21 days.

But when did the Polynesians settle Rapa Nui? Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) now allows the dating of samples as small as a single seed, which means that dates for initial colonization will become ever more precise. For reason, Rapa Nui has become a fashionable destination for archaeologists in recent years, probably because of the spectacular moaie – ancestral statues that gaze enigmatically to the far horizon.

In a recent archaeological tour-de-force, the University of Hawaii archaeologists Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo have excavated a stratified sand dune, which dates first settlement to AD 1200, the late Medieval Warm Period. This date squares with new readings from other Polynesian islands, which were settled at about the same time, apparently a time of greater El Niño activity. Thanks to a revolution in climatology, we now know the historical power of major El Niños, which killed over 20 million tropical farmers during the 19th century alone. They are second only to the seasons in their influence on global climate. We ignore the subtle influence of climate on ancient societies at our peril.

How the Norse nailed it

Iron nails are not exactly a stimulating historical topic, but they should be. The Norse colonized Greenland during the warmer medieval centuries but they could not have done it without nails.

Like all working craft, Norse ships were disposable artifacts, with a shelf life of about ten years’ hard use. Their timbers might split and rot away, but what about the nails that held the planks together?

Olaf Envig is an expert on Norse ships with an interest in iron. Every Norse farm had its own smithy to work the bog iron that abounded in swampy northern forests. Envig believes that the Greenland Norse built their new ships in remote Labrador bays. There they cut down trees and split planks. There, too, they smelted the hundreds of iron nails for the new hull from local bog iron. But they were thrifty folk with an eye for a profit.

Envig believes the skippers pulled their old hulls apart and recycled the iron. They carried it home, then traded the old nails to Inuit groups in Baffinland and elsewhere on their sporadic expeditions in search of walrus ivory to pay church tithes in far-away Norway. We may never be able to document this ingenious theory, for the Norse left little behind them in Labrador. Here, as elsewhere, the archaeological signature that remains for us is baffling, and often virtually invisible. Archaeology is deeply satisfying, but is all too often just plain frustrating.

What solution Stonehenge?

Cultural tourism is said to be the fast growing segment of the international tourist economy, and that archaeology is at the centre of it. When visitor counts at places like Angkor Wat and Ephesus are in the hundreds of thousands and rising, one wonders what the future is.

Returning to Stonehenge, it has an annual count of some 850,000 paid visitors, a startling figure given the rudimentary and frankly disgraceful facilities at this greatest of all British archaeological sites. Plans for improvements involve major and expensive road modifications. The British Government has accepted an ambitious plan that involves a 2km tunnel for a main trunk road to southwestern England that passes by the site. English Heritage plans a world-class visitors’ centre and a ‘land train’ to carry tourists to the stone circles. This way, visitors will appreciate Stonehenge not just as a site, but as a place set in a sacred landscape.

The cost of this scheme, which is a compromise between many stakeholders, is £510 million for the road work alone. So far the British Government has maintained an opaque silence on funding, despite the valiant efforts of the local Member of Parliament, Robert Key. He has written to UNESCO recommending that Stonehenge lose its World Heritage Site designation on the grounds that the Government is not fulfilling its obligation to improve access to the area for the general public. Good on Robert Key, whose timely letter has caused a considerable stir in the dovecotes of UNESCO and the British Government. The latter has claimed that they are making ‘progress’, which is perfectly true – up to a point. But is it not time the Government stepped up to the plate and invested in Stonehenge for future generations? Apart from being a masterly political gesture in support of heritage, the longterm economic benefits of investing in one of the best loved sites in the world are enormous. The ball is firmly in the hands of the British Prime Minister and the Treasury. Please keep up unrelenting pressure in the right places, Mr Key! Flights between London and Los Angeles are interminable. Nadia told me to make good use of my time and write this column on the plane, and I’ve been a good boy and done so, despite having lost my glasses. Now my neighbour is taking an unhealthy interest and starting to murmur about dinosaurs… I’m going to take refuge in Julian Richards’ book on Stonehenge. Only four hours to go!

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 26. Click here to subscribe