With a story stranger than fiction, the first Englishman to make the Islamic pilgrimage was Joseph Pitts of Exeter (c.1663-1739). Though he was probably not really the first, he was the first to write an account, in English, of the Hajj. His is an extraordinary book. Not only does he provide the earliest English insider’s description of Muslim customs and society, but he offers a page-turning read involving kidnap, cruelty, and a trek across Europe.

With a story stranger than fiction, the first Englishman to make the Islamic pilgrimage was Joseph Pitts of Exeter (c.1663-1739). Though he was probably not really the first, he was the first to write an account, in English, of the Hajj. His is an extraordinary book. Not only does he provide the earliest English insider’s description of Muslim customs and society, but he offers a page-turning read involving kidnap, cruelty, and a trek across Europe.

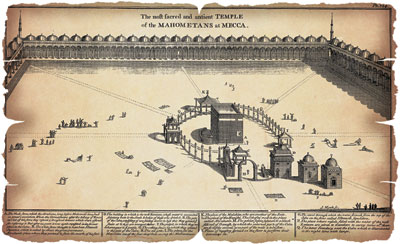

Born in Exeter, Joseph Pitts had a basic education before going to sea as a boy. However, on his very first voyage in 1678, his small fishing boat was captured off the coast of Spain by an Algerian corsair vessel. Its Muslim captain turned out to be a Dutchman and its first mate an Englishman. Sold twice as a slave in Algiers, to cruel masters, Pitts underwent forced conversion to Islam. Sold once more, he accompanied his kindly third master on pilgrimage to Mecca, in 1685 or 1686. The pair arrived in Jiddah by dhow from Suez, and then spent about four months in Mecca before going on to Medina.

A pilgrim’s progress

After completing the Hajj, Pitts was granted his freedom. Thereafter, he spent several years serving as a soldier in Algiers, before venturing on an audacious escape while serving at sea. Crossing much of Italy and Germany on foot, he finally returned to England some 17 years after he had first left. With unbelievable bad luck, on his first night on native soil he was press-ganged into the navy. Thankfully, following appeal, he was released, and Joseph Pitts went on to write of his experiences in his book A Faithful Account of the Religion and Manners of the Mahometans, published first in 1704 and then again, in a fuller version, in 1731. This has now been republished, together with an extensive commentary by the acclaimed Arabic scholar, Paul Auchterlonie, under the title Encountering Islam; Joseph Pitts: An English Slave in 17th-century Algiers and Mecca.

As the title of Pitts’s original book suggests, he covers almost every element of Muslim ‘religion and manners’ – including the first-ever description (in English) of the holy sites of Mecca and Medina, but also taking in everything from Muslim daily ritual and practice, which he describes exhaustively, to Turkish cuisine and Algerian childcare, via wine, women, and wrestling. Through all of this, one of Pitts’s recurring themes is his admiration of Muslim devoutness and punctilious adherence to their rules and rituals, which he holds up as an example to Christians. He writes movingly of the pilgrims’ deep emotions as they performed the Hajj. He also speaks of his inner turmoil on his return to England, where he rediscovered Englishness and returned to Christianity. In Pitts’s time it was difficult to identify oneself as English and non-Christian without incurring ostracism, or worse. His internal struggle between these two identities runs through his book – from the love he had for his childless third master, who treated him like a son, to his renewed allegiance to Christianity. He ends his book with a prayer to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Lady Hajji

But what about the first British female hajji? As acknowledged in the recent British Museum exhibition, Lady Evelyn Cobbold (1867-1963), Mayfair socialite, owner of an estate in the Scottish Highlands, mother, gardener, and accomplished deerstalker, was – as far as anyone has been able to establish – the first British-born female Muslim convert to record her pilgrimage to Mecca.

Fluent in Arabic, Lady Evelyn became a hajji in 1933, as a wealthy 65-year-old. She published her account, Pilgrimage to Mecca, notable for its sympathy and vividness, the following year. Her book enjoyed brief popularity but was later forgotten, until 2008 when it was reprinted. In it she promotes Islam for its simplicity and tolerance, describing it as ‘the religion of common sense’. Interestingly, she also provides the first description by an English writer of the life of the women’s quarters of the households in which she stayed. An associate of both T E Lawrence and Philby (father of the spy), she lived another 30 years after her pilgrimage, and was buried as a Muslim on a remote hillside on her Glencarron estate. Her splendidly Islamo-Caledonian interment symbolised her two worlds: a piper, so frozen that he was hardly able to play, performed ‘MacCrimmon’s Lament’, while a verse from the Qur’an was loudly recited by an equally refrigerated Imam of the Working Mosque. That verse adorns her grave, over which deer now wander, according to her wishes. Though these two hajjis had very different backgrounds and stories, their books breathe life into the past. Their words allow us to understand something of the pilgrim’s individual spiritual journey, while also shining new light onto Islamic society and history. And though the British Museum exhibition is now finished, their stories are still there for the reading.

This feature draws extensively on a special lecture given by William Facey at the British Museum, February 2012.

FURTHER INFORMATION: Two books written by the first-known British male and female hajjis are newly republished: Paul Auchterlonie, Encountering Islam; Joseph Pitts: An English Slave in 17th-century Algiers and Mecca. Hardback, illustrated. Arabian Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978-0-955889493, £48.00 (or £35.00 incl p&p for UK-based readers of CWA). Lady Evelyn Cobbold, Pilgrimage to Mecca, with an introduction by William Facey and Miranda Taylor. Paperback, 50 photographs. Arabian Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-0-955889431, £20.00 (or £18.00 incl p&p for UK-based readers of CWA). To enjoy the CWA special offer, quote ‘CWA offer’ and send your name, address plus a cheque for the reduced amount made out to Arabian Publishing Ltd, 4 Bloomsbury Place, London WC1A 2QA.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 53. Click here to subscribe