South Asia has long been known for having one of the greatest assemblages of historic monuments in the world. There is no shortage of books that illustrate them magnificently. But there are few good books on the development of South Asian archaeology with lavish period photographs superbly reproduced in a large format. The Marshall Albums is therefore a welcome newcomer.

South Asia has long been known for having one of the greatest assemblages of historic monuments in the world. There is no shortage of books that illustrate them magnificently. But there are few good books on the development of South Asian archaeology with lavish period photographs superbly reproduced in a large format. The Marshall Albums is therefore a welcome newcomer.

Sir John Marshall was probably the most significant archaeologist to have worked in India, though less well known than the younger Mortimer Wheeler. Marshall was the longest-serving director general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) – founded by Alexander Cunningham in 1861, it is 150 years old this year. Appointed by the Indian viceroy Lord Curzon in 1902 at the age of 26, Marshall remained in post until 1928, and continued to work for the ASI until 1934. Between 1902 and 1928, he oversaw seminal excavations at 49 sites across the subcontinent, from Taxila in today’s Pakistan to Sanchi and Sarnath in India, and Pagan in Burma (but little in south India and nothing in Ceylon). He is best known for his revelation of India’s earliest civilisation at Mohenjodaro in the Indus valley, which he announced to the world in 1924 in The Illustrated London News as follows: ‘Not often has it been given to archaeologists, as it was given to Schliemann at Tiryns and Mycenae, or to Stein in the deserts of Turkestan, to light upon the remains of a long-forgotten civilization. It looks, however, at this moment, as if we are on the threshold of such a discovery in the plains of the Indus.’

The Marshall Albums is based on Marshall’s personal collection of photographs, consisting of family photographs and those from the ASI’s photographic archives, supplemented by images from elsewhere and complemented by five essays written by five different scholars responding to the photographs, under the editorship of the Cambridge-based historian Sudeshna Guha.

This primary collection is kept in New Delhi in the Alkazi Collection of Photography. A second collection, donated by Marshall in 1954, resides partly at Durham University and partly at Cambridge University in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. Also used in the book is a further Cambridge University collection, kept at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, which includes the photographs of the civil engineer Frederick Oscar Lechmere-Oertel, who supervised the ASI’s excavations at Sarnath in 1904-1905 and the repairs to the Agra fort in 1905-1906, and those of Harold Hargreaves, who succeeded Marshall as director general of the ASI in 1928.

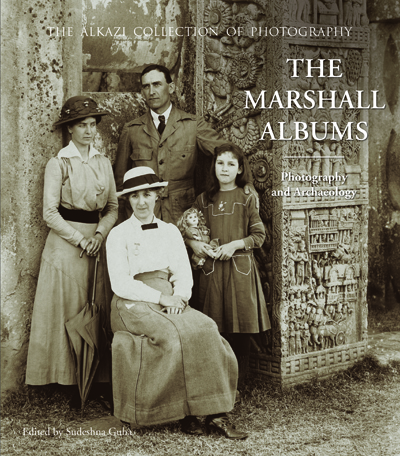

The Marshall family photographs begin the book and provide an appropriate setting for the archaeological images. Without overdoing the atmosphere of the British Raj, they conjure up a bygone colonial age of de rigueur sola topees (pith helmets), dusty bungalows in the plains, cool hill stations, uniformed servants, and stuffy viceregal parties. We see Marshall and his wife posed in an official photograph taken with the officers and staff of the ASI at Simla in 1925. Another, taken by Marshall, catches the Prince of Wales playing croquet at Taxila in 1922. A third shows Marshall and his family all dressed in white, seated before a retinue of standing Indian servants and two hulking, caparisoned elephants with their mahouts at the Sanchi Archaeological Camp in 1912-1914. Holiday photos show the Marshall family on a houseboat floating on the Dal Lake in Kashmir, and Marshall, his wife, his young daughter, and her governess (holding a large furled sun umbrella) grouped within the beautifully carved eastern gateway of the Great Stupa at Sanchi, which Marshall excavated and conserved over many seasons.

Most of the book’s photographs show buildings and sites, however, in the process of either excavation or restoration. Whilst these activities, and the images themselves, were undoubtedly the products of colonialism, the photographs ‘should not be read as interpretations of the “colonial gaze”’, Guha rightly stresses in her introduction to the book. ‘Rather, they ought to be perceived as artefacts of archaeological practice that endowed archaeology with the values of a unique disciplinary science.’

Nonetheless, Imperial requirements drove much of the activity of the ASI, especially with regard to the conservation of the splendid Mughal heritage that directly preceded British rule in India. Curzon directed that the broken minarets on the entrance gate to the tomb of the Mughal emperor Akbar at Sikandra be repaired in time for a visit by the Prince of Wales in 1905, so that the prince ‘could see what no one has seen for a century and a quarter’.

The garden party held in Delhi in 1911 in honour of King George V and Queen Mary took place in the Hayat Baksh, the gardens of the Red Fort created by the Mughals and restored at great expense by the ASI over a period of ten years beginning in 1903. In 1926, after the ASI had repaired the Lahore Fort, a viceregal Durbar took place there and was described in the ASI’s annual report ‘as the first Imperial Durbar held there since the time of the Emperor Aurangzeb’. In other words, writes Guha, ‘Curzon’s self-laudatory proclamations of leaving an enlightened legacy of a cultured British rule within India through archaeological restorations clearly articulated Britain’s own imperial aspirations.’

Marshall did his duty by the Mughals – witness the photograph of the Taj Mahal after removal of ‘superfluous trees and shrubberies’ taken in 1915-1916, or the view of Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi with restored tank and gardens, taken in 1923-1924 – but his heart could be said to have lain elsewhere, much further back in the long history of the subcontinent.

The common link between the three sites where Marshall personally excavated for long periods, Sarnath (1906-1908), Sanchi (1912-1919) and Taxila (1913-1917, 1919-1934), was his interest in Buddhism. It is therefore the archaeology of Buddhist sites – especially his work at Sanchi – that provides the book with a unifying theme and its most striking photographs. Indeed, three of the book’s five essays specifically concern Buddhism: The many lives of the Sanchi Stupa in colonial India by Tapati Guha-Thakurta, ‘Buddhist’ photography by Christopher Pinney, and the insightful Cunningham, Marshall, and the monks: an early historical city as a Buddhist landscape by Robert Harding. Marshall, like many British scholars of the 19th century in India, including the founder of the ASI, Cunningham, was drawn to the rationality and ethics of Buddhism, and its opposition to caste and empty ritual. In an early ASI annual report on Rajgir and nearby Grdhakuta (the ‘Hill of the Vultures’), where Gautama Buddha spent several months meditating and preaching, Marshall even went so far as to suggest that: ‘it would be worth while trying to find the stone on which Buddha walked up and down for exercise, the great rock said to have been flung at him by Devadatta, the hole in the rock through which Buddha stretched his hand to pat Ananda’s head, and the rock in the stream on which Buddha dried his garment.’

Not all of The Marshall Albums is as accessible as this. In places, the writing suffers from the opaque jargon regrettably favoured by many specialists in South Asia, anthropology, and media studies. But most of the text is enlightening, and almost all of the illustrations are well chosen, fascinating, and full of detail. For anyone interested in the history of Indian archaeology, this book is a ‘must’.

Andrew Robinson is the author of several books on Indian history and culture. His next book is a biography of Jean-François Champollion.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 48. Click here to subscribe