Sir Aurel Stein is one of the least known of the Great British Archaeological explorers of the earlier 20th century. He was, in fact, a Hungarian Jew, born in Budapest in 1862, though his parents prudently had him baptized into the Lutheran Church. After studying Sanskrit at Vienna, Old Persian at Tubingen, and Punjabi at Woking, he moved to India where he spent most of his life, nominally in various academic posts but really sweet-talking his superiors and supporters into providing funds; with these he launched expedition after expedition into Central Asia to explore what a German geographer, von Richthoven had in 1877 called the Silk Road (Seidenstrasse). He befriended Layard Kipling – Rudyard’s father – who was curator of the Lahore museum, and taught himself archaeology by studying the reports of Flinders Petrie.

Sir Aurel Stein is one of the least known of the Great British Archaeological explorers of the earlier 20th century. He was, in fact, a Hungarian Jew, born in Budapest in 1862, though his parents prudently had him baptized into the Lutheran Church. After studying Sanskrit at Vienna, Old Persian at Tubingen, and Punjabi at Woking, he moved to India where he spent most of his life, nominally in various academic posts but really sweet-talking his superiors and supporters into providing funds; with these he launched expedition after expedition into Central Asia to explore what a German geographer, von Richthoven had in 1877 called the Silk Road (Seidenstrasse). He befriended Layard Kipling – Rudyard’s father – who was curator of the Lahore museum, and taught himself archaeology by studying the reports of Flinders Petrie.

Of his various expeditions into Central Asia, the most important and controversial was the second when he penetrated through to Dunhuang in the westernmost province of China. This had been a major Buddhist station where a colony of monks had lived in caves from 800-1200 AD. One of the caves, full of Buddhist manuscripts and drawings, had been plastered over but had recently been rediscovered by the monks. Stein was taken to see them, but was appalled at the poor condition they were in and feared that they would soon be destroyed or dispersed. He offered to buy the entire contents for 40 silver horseshoes – he travelled with a supply of silver horseshoes which could always be cut up by the local blacksmith en route when payment was needed. Eventually the custodian monk agreed to sell a small portion for four silver horse shoes, though eventually Stein managed to bargain for more. He then had to struggle back to India with his collection, though on the way back he spent so long crouched over his surveying table in the freezing mountain passes, that his toes were frost-bitten and had to be amputated to prevent gangrene. When he eventually arrived back his finds were divided, three-fifths going to New Delhi and two-fifths to the British Museum, where they still form the most important single source of information about Buddhism and many forms of Chinese life and art in the Tang Dynasty.

He was always accompanied on his expeditions by his dog, Dash, though there were in fact seven successive dogs, all called Dash, all of whom happily trotted over the high Himalayan passes; though it should be recorded that Dash II was run over by an Oxford bus in 1918, and in 1941, Dash VI was eaten by a leopard.

In 1928 he formally retired, but after being barred from work in China, he turned his attention to the Middle East and began work in Iraq and Iran. By the late 1930s – by now well into his 70s – he discovered aerial archaeology and soon became one of the pioneer aerial archaeologists, notably discovering the Roman Frontier works in the area. But there was one country he had still not visited – Afghanistan. In 1943 he eventually managed to gain permission to travel there, but within a week of his arrival he fell ill, and eventually, on 26th October 1943, he died in Kabul, where he is buried.

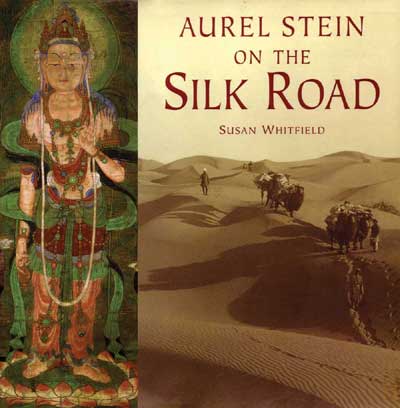

Susan Whitfield who works in the British Library, where she is Director of the International Dunhuang project which is busy putting all his Dunhuang studies on the internet, has written an exemplary study of Aurel Stein entitled Aurel Stein on the Silk Road, published by the British Museum Press, price £18.99. This is in essence a fairly slim volume; it is elegantly printed in a large typeface well leaded out, and illustrated with superb photographs, both from his own collections, and with new colour photographs of his numerous finds. It is thoroughly recommended to all connoisseurs of the Silk Road, and to those who like to read a fascinating account of a meticulous adventurer, who spoke a wide range of languages, made marvellous maps, wrote both impeccable reports and popular books – as well as becoming one of the British Museum’s most important donors.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 7. Click here to subscribe